Lily Carhart, Curator of Preservation Collections, George Washington’s Mount Vernon

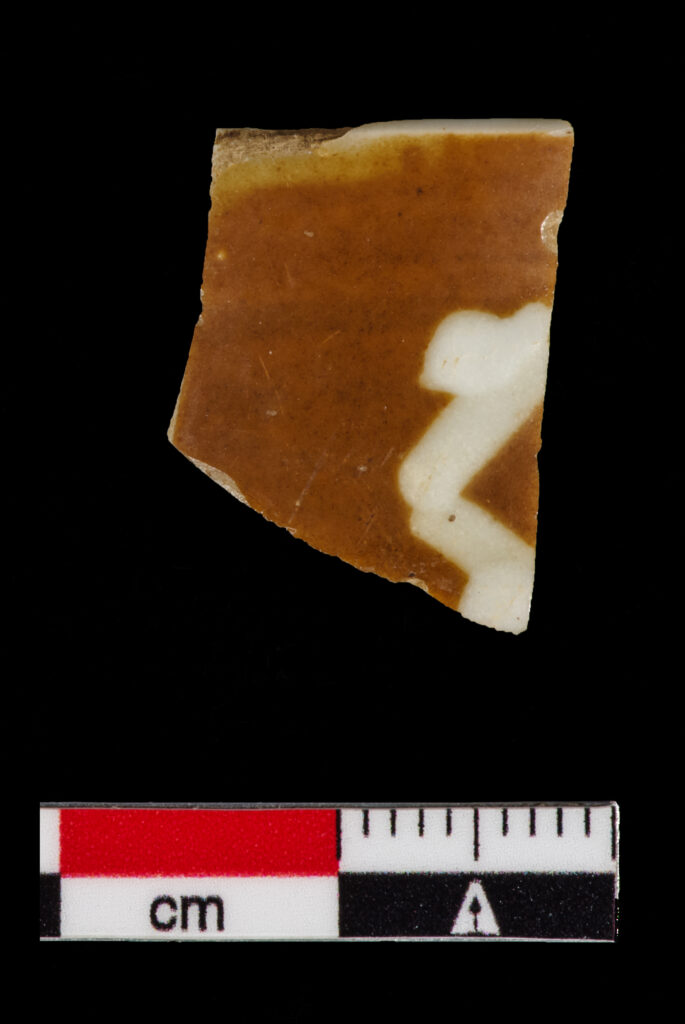

In 2019 while cataloguing and photographing artifacts from recent excavations at George Washington’s Mount Vernon in the area south of the Kitchen outbuilding, a member of the archaeology team identified a tobacco pipe stem stamped with an elaborate coat of arms. This discovery started a multiyear journey into studying the origins and significance of pipes with this stamp.

The stamp had been found previously on a couple pipe stems at Mount Vernon from a midden, located roughly 30-40 feet from where the new pipe was discovered. Originally, the mark was identified as depicting a scene from Aesop’s fable about the Fox and Grapes. However, new research identified the coat of arms as belonging to the Worshipful Company of Ironmongers, one of London’s “Great 12 Livery Companies”. The Livery Companies are trade associations or guilds with origins in Medieval London and still exist today! The Ironmongers’ coat of arms consists of a shield emblazoned with gold swivels or chain on a red chevron, surrounded by three gads, or ingots of steel. Above the shield are two salamanders that have been tamed and collared, the chain hanging between them representing the iron workers’ ability to tame and harness the transformative power of fire to work metal.

After this discovery, The Mount Vernon Archaeology team searched through legacy collections to locate similar pipes and found an unexpected yet illuminating connection. Another pipe stem is marked with not only the Ironmongers coat of arms but also the coat of arms of the City of London! This pipe allowed us to connect four separate stamps that had been found in different combinations on pipes from areas all around George Washington’s mansion. The other stamps include one that reads “GRAHAM / WHITE / CHAPPEL” with one heraldic or spearhead band. To date, 17 tobacco pipe stem fragments with one or more of the three unique stamps have been identified, including one that has at least a portion of all four stamps. We have yet to connect a bowl or heel fragment to any of the stems.

Although the oval shape of the stamps was almost exclusively used by Chester pipemakers, the content of every stamp, as well as the styling of the lettering, references London. This indicates that these pipes were likely made in London by Anthony Graham, a pipemaker who lived in Whitechapel in the second quarter of the 18th century.

So, how and why did these pipes come to be at Mount Vernon? The use of a guild’s coat of arms was tightly controlled in the 18th century. These pipes were likely commissioned by an individual or organization directly connected with the Ironmongers. George Washington’s father, Augustine, was an investor and partial owner in the Principio Company, which operated multiple blast furnaces in Virginia and Maryland and exported large quantities of pig iron to London Merchants. Augustine traveled to London in the course of this business and perhaps interacted or engaged with members of the Worshipful Company of Ironmongers and encountered these pipes. However, if this interaction did occur, no documentary evidence has been found so far.

While only four of these pipes were found in intact 18th century contexts, these layers all contained artifacts that date to the mid-18th century, when Augustine or his son Lawrence’s households occupied Mount Vernon, and when Anthony Graham was manufacturing pipes in Whitechapel.

Hopefully, additional pipes will be recovered in future excavations or new documents will be revealed that help solidify or clarify some of these possible connections and help us to answer our lingering questions about how and why these Ironmongers’ tobacco pipes were at Mount Vernon in the 18th century.

Thank you to Sierra Medellin who conducted a significant portion of this research and for making the initial identification of the Ironmongers’ coat of arms!

References

Atkinson, David, and Adrian Oswald. London Clay Tobacco Pipes. London: Museum of London, 1970.

Bennett, Kirsty. The Cardew-Rendle Roll: A Biographical Dictionary of Members of the Honourable Artillery Company from c. 1537-1908. London: Honourable Artillery Company, 2013.

Higgins, David. “Surrey Clay Tobacco Pipes.” The Archaeology of the Clay Tobacco Pipe: VI Pipes and Kilns in the London Region, BAR British Series97, 1981, 189–293.

Jeffries, Nigel. RE: Marked Pipe Inquiry from George Washington’s Mount Vernon, March 11, 2020, personal communication.

Oswald, Adrian. Clay Pipes for the Archaeologist. 14. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 1975.

Parish, Preston, and Maryland Historical Trust. “Principio Furnace.” National Register of Historic Places Registration, June 1971.

Stedall, Robert, and Justine Taylor. One Hundred Treasures of the Worshipful Company of Ironmongers. London, Worshipful Company of Ironmongers, 2016.

Taylor, Justine. RE: Tobacco Clay Pipes with Your Livery Company Coat of Arms…?, January 22, 2020, personal communication.

All images courtesy of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association with the exception of Image 2.

Image 2: Lon-Ironmongers. 2014. Heraldry Wiki. https://www.heraldry-wiki.com/heraldrywiki/wiki/File:Lon-ironmongers.jpg#filelinks.