Caroline Gardiner, Veteran’s Curation Program

“What’s the date for our coin?”

“1790s.”

“They have the same one.”

In 2021, the Veterans Curation Program (VCP) in Alexandria received a 260-box collection from the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) Norfolk District’s Gathright Dam/Lake Moomaw project. The Dam is located in west-central Virginia about 40 miles from Staunton. The area’s history covers thousands of years, resulting in a mixed assemblage from pre-Contact sites to 19th to 20th-century coal mining towns and farmsteads. The collection also includes a vast amount of archival records ranging from 1800s census records to field forms.

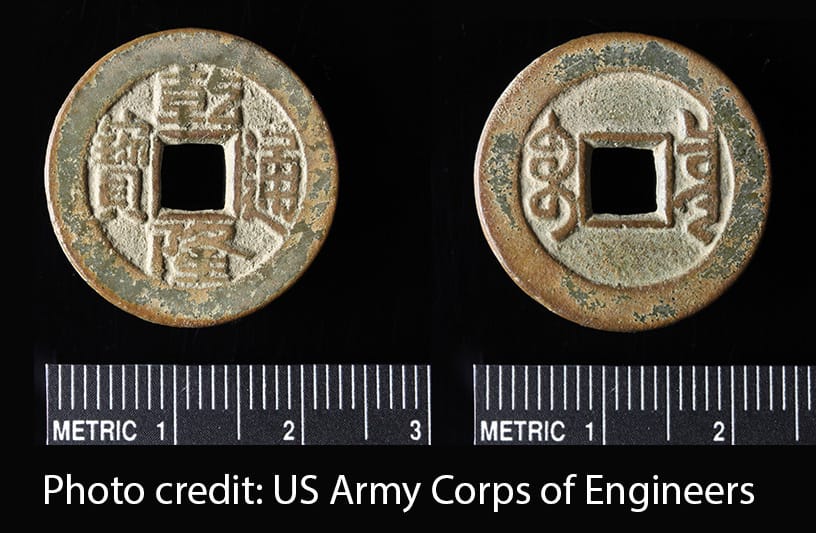

The VCP hires veterans to help care for at-risk USACE collections including artifact rehousing, cataloging, and photography. While working through the first Gathright boxes, technicians came across a small copper alloy Chinese coin. Its symbols spell out “Qianlong Tongbao,” translating to Emperor Qianlong (reign 1735-1796) and “coin.”[1] So how did it come halfway across the world to end up in the Appalachian Mountains?

Not long after beginning research on the coin for this newsletter, the Alexandria VCP team took a field trip to the nearby Freedom House Museum. One case displayed artifacts recovered in the 1984-5 excavations, including another Qianlong coin. What were the chances? And what did it mean for the Gathright coin interpretation?

The team hypothesizes four possible scenarios. To begin with the simplest, the Gathright coin is generally provenienced to a late 19th/early 20th-century house area, while the Alexandria example was recovered from post-Civil War fill in a dry well/privy.[2] While it is possible that Chinese individuals lived in the Gathright area, so far no records of them have been found in the site reports, census records, or land ownership documentation within the VCP archival collection. However, previous research into Alexandria archives revealed a steady growth of Chinese immigrants in that city throughout the 19-20th centuries, with many establishing laundry businesses.[3] It is possible that residents brought these coins with them and merely lost or discarded them.

Second, both sites also have connections to railroads. The Shenandoah Railroad, completed in 1882, ran parallel to the Blue Ridge from Roanoake, VA to Hagerstown, MD with extensions reaching to Alexandria and DC. The 1880 Wheeling Register recorded “three hundred hands, including twenty-five Chinese” working near the Hagerstown stop.[4] They were among the thousands of Chinese laborers who built railroads across the entire United States (the Transcontinental Railroad had been completed only a decade before). It is entirely plausible that the owners of these coins were laborers following projects eastward.

Trade is another possible explanation, especially given Alexandria’s status as a port city. Several 20th-century oral histories of the Gathright area mention harvesting ginseng (or “sanging”).[5] The Appalachian ginseng trade developed in the 19th century and continues to be a cash crop today. Ginseng was transported to cities and as far as China where demand was high.[6] Could the coins be results of these interactions?

We also cannot rule out simple collection. These coins symbolize foreign places and may have been used as “objects of curiosity” to display personal status or connections. They conveniently are already pierced and could have been worn on a string as a souvenir or luck charm. What was once, then, an everyday item of exchange became something personal and extraordinary. We can only speculate.

[1] Cao, Qin. “An Introduction and Identification Guide to Chinese Qing-Dynasty Coins.” National Museums Scotland. 2014. <https://www.nms.ac.uk/media/1161122/an-introduction-and-identification-guide-to-chinese-qing-dynasty-coins-qin-cao.pdf.> Accessed 23 August 2022.

[2] Artemel, Janice G., Elizabeth A. Crowell, and Jeff Parker. The Alexandria Slave Pen: The Archaeology of Urban Captivity. Engineering Science, Inc. Washington, D.C. 1987.

[3] “Chinese Immigrants in Alexandria, VA.” Immigrant Alexandria Project. University of Mary Washington. 2016. <http://immigrantalexandria.org/chinese-immigrants-in-alexandria-va/.> Accessed 23 August 2022.

[4] Fisher Fishkin, Shelley. “Bibliographic Essay for The Chinese as Railroad Workers after Promontory.” Chinese Railroad works of North America Project. Stanford University. 2019. <www.chineserailroadworkers.stanford.edu.> Accessed 10 September 2022.

[5] Campbell, Dana, Norman Dean Jefferson, Clarence R. Geier, Bernadine McGuire, and Elwood Fisher. An Historic Commentary of the Jackson River Valley, Bath and Alleghany Counties, Virginia. Report submitted to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Norfolk District. Occasional Papers in Anthropology (13). James Madison University. 1982.

[6] Library of Congress. “American Ginseng and the Idea of the Commons: Historical Background.” Tending the Commons: Folklife and Landscape in Southern West Virginia in the Coal River Folklife Project Collection. Library of Congress American Folklife Center. 1999. <https://www.loc.gov/collections/folklife-and-landscape-in-southern-west-virginia/articles-and-essays/american-ginseng-and-the-idea-of-the-commons/historical-background/.> Accessed 5 September 2022.